“Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and aesthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient.”

See

What is consumer purchasing? It seems a somewhat nebulous term and is inclusive of many different facets of our lives. In broad strokes, it is all the items that we use in our daily lives. It includes the clothing we wear, the electronics we use, and the appliances we buy. They are items that you use every day, and, much of the time, hardly notice. Yet each of these items has a story, ranging from the resource extraction of its base materials, through manufacturing and distribution, to your purchasing and using the item, to its end-of-life once you are through with it. Generally, in the grand scheme of a product’s lifetime, the time it spends in the consumer's possession is fleeting.

To better understand the impacts of our collective buying preferences, we need to begin to think about the entirety of a product's life-cycle and, to do so, here is a little thought experiment. Choose a typical household item, it could be a toaster, toothbrush, a jug of bleach, or anything else. Ask yourself, or better yet, ask someone else and think through it together, some of the following questions.

Is this item a want or a need?

What are the effects of the item, both positive and negative, on you, other people, animals, and the environment?

What systems support, promote, and perpetuate this item?

What would be an alternative item, or a change to a system, that would do more good and less harm?

Once you have thought through it, reflect on your answers. This activity designed to help narrow into an item’s “True Price”. Not the sticker price, but some of the externalities that lie just below the surface.

So why focus on consumerism?

As the global population has grown, and technology has progressed apace, global affluence has exploded. It is not a universal growth, as many parts of the world remain under-represented in this economic growth, but the trend of distributed affluence across the world population has not only grown, but is accelerating.

As many of those who have calculated their ecological footprint will have seen, as more and more people move toward economic prosperity and stability, there is an associated unsupportable resource demand. Approximately 1.7 billion people worldwide now belong to the "consumer class", the group of people characterized by diets of highly processed food, desire for bigger houses, more and bigger cars, higher levels of debt, and lifestyles devoted to the accumulation of non-essential goods. If today nearly half of global consumers reside in developing countries, including 240 million in China and 120 million in India (markets with the most potential for expansion), then only through a careful re-tooling of our consumer practices can we make the societal and global shift from traditional “Take, Make, Waste” consumerism to Sustainable consumerism.

The traditional paradigm of consumerism is one of Take (resource extraction), Make (production and distribution), and Waste (use and end-of-life). It is the means by which we have produced goods since the turn of the industrial revolution. It is a linear flow of limited resources and, even if the initial reservoir of resources is enormous, the one-directional flow never allows for replenishment. Additionally, even as the source is reduced, the waste grows.

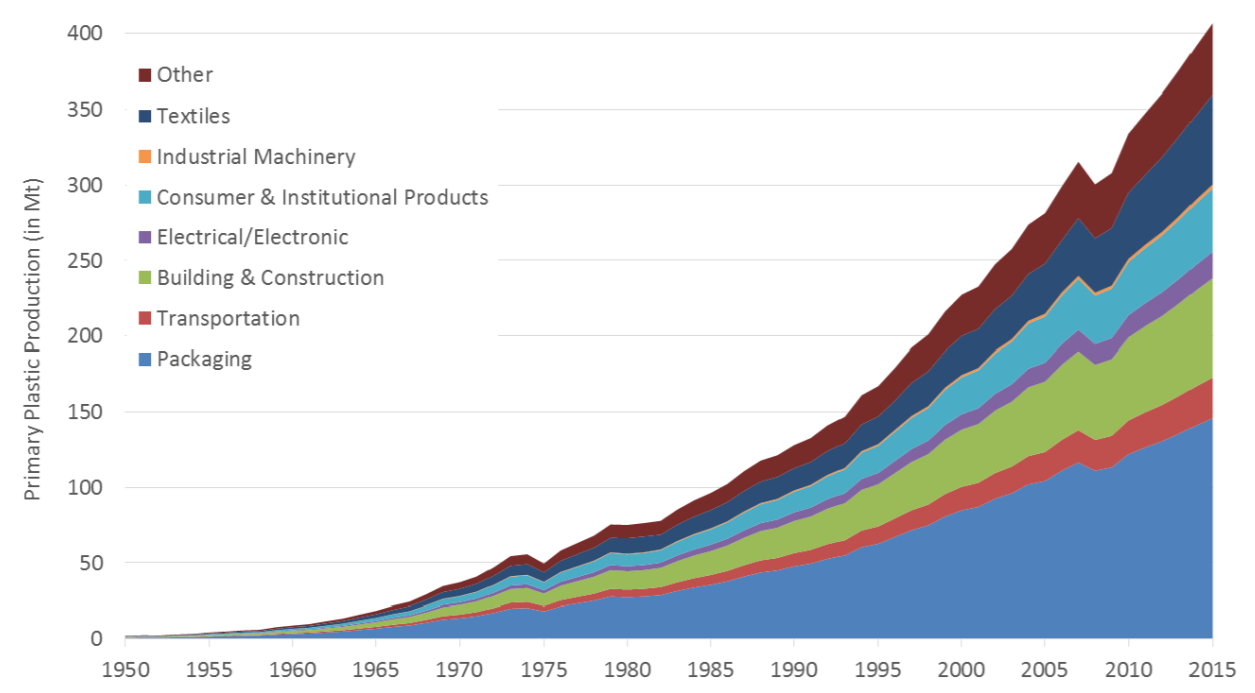

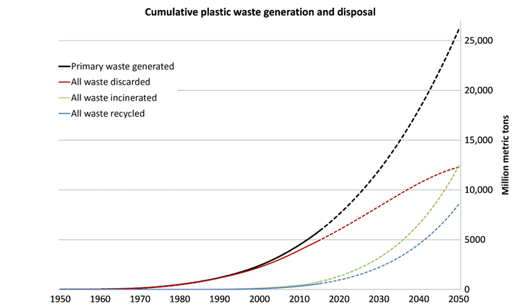

Take, for example, plastics. While there has been an enormous push, from a cultural standpoint, to promote recycling, the majority of plastic generated still ends up incinerated or discarded. To begin to shift from traditional consumerism to sustainable consumerism, we need to take a closer look at the product life-cycle, and how more sustainable methods and operations can be introduced. Broadly, it is both a matter of design and user preference.

Consider a seemingly simple item, like a white cotton shirt. Does it seem more likely that, in our daily lives, it simply goes to the landfill after use? Does the reduce, reuse, recycle portion of the life-cycle seem almost like an afterthought?

Not only is there an inherent issue with the sourcing and design of resource use in the products we buy, but there is also the issue of obsolescence. Obsolescence is the process of an item/technology being replaced, outdated, or falling out of use. We interact with the concept of obsolescence in our lives in various ways, but chiefly in three broad categories:

Obsolescence of desirability (the latest “fad”)

Obsolescence of durability (goods not made to last)

Obsolescence of non-compatibility (older tech not compatible with newer services)

Each of these have social, economic, and technological aspects, and each of them can be combated to various degrees of success by consumers. Take obsolescence of durability, for example. If the intention of the designer, consistent with the desire of the consumer is the lowest possible price of the product, then the resulting product will have a lower initial cost but will have higher replacement or environmental costs. While the cost of a higher quality product is felt more sharply at the onset, the environmental cost and replacement cost will be lower than the cheaper, lower quality, product. This is not universally true of all products, but it is a good rule of thumb.

For all three analyzed products, the ultimate environmental impact of the long-lived products was lower than the short-lived products, in no small part due to the replacement requirements.

Each of us, as members of the global society, need to push ourselves to reduce the impacts of our purchasing practices.

Discern

We have discussed the status quo, but why are we obligated to make changes in our life to reduce the impacts of our consumer purchases? Because there will be consequences to inaction and these consequences will be felt personally, in our communities, in our states, in our country, and in our world.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015, provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. At its heart are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are an urgent call for action by all countries - developed and developing - in a global partnership. They recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests.

The goal most pertinent to the discussion of consumer purchases is goal twelve.

Context, as ever, is king when discussing what we must do to combat the impacts of our purchasing choices. To provide this context, and why Americans and others who live in economically developed countries must take action, take the following example. Two families, one in Mali and the other in America, are invited to participate in an expose on the difference in people's lives around the world. As part of the expose, all the material possessions for each family were itemized and placed outside their home. The following two photos should provide some insight as to who should take on the lion’s share of the responsibility for change.

SO WHY TAKE ACTION?

There are many universal and interrelated principles that should guide every person in how they interact with the world around them, especially in regards to activities and actions that have the potential to have a disproportionate impact on those less fortunate than themselves. These principles are areligious, apolitical, and cross-cultural and national borders. When deciding on whether or not to take action in your own life and take that first step toward sustainable living, consider if these four principles that we have identified have meaning to you.

Human Dignity

Our fundamental worth is not earned but is inextricably part of being human and inherent in each person.

Common Good

Common Good is the measure of our collective progress towards creating conditions that allow everyone to flourish.

Solidarity

Solidarity is the firm commitment to the good of each person and of all because we are all deeply interconnected and interdependent with not only each other but all of life.

Subsidiarity

Subsidiarity is the belief that matters are to be handled at the lowest level possible and the highest level necessary, in order to allow each part of the social order to receive its due so it can carry out its proper function.

If these principles are in line with your beliefs and identity, then how can we not take action?

Action

Fortunately, or unfortunately, there is enormous nuance in how we, as individuals, communities, and societies can reduce the impacts of our purchases and many will have heard of the term “Green Consumerism”. The classical paradigm of green consumerism focuses on how consumers seek to purchase “eco-friendly” alternatives but do not necessarily change their overall level of consumption. However, the deeper, more impactful form, is where consumers seek to purchase eco-friendly alternatives but also, more importantly, seek to reduce their overall level of consumption. Why? Consider again the take, make, waste system. Even if it shifts to close the loop, to re-use and recycle the waste back into the take, there can’t help but be loss. In reality, often, but not always, the most eco-friendly product is the product that was never made.

Reduce, Reuse, Recycle are anything but equal.

Consistent with this, what are some actions you can take?

Personal

Buy Fewer Items

Choose Longer Shipping Times

Donate/Buy Clothes at Resale Shops

Repair Clothes Rather Than Buy New

Personal

Bring Reusable Bags When Shopping

Shop for Products with Recycled Materials

Identify Products that have Lower Environmental Costs (Ex; Good Guide)

Ask to be Removed from Paper Mailing Lists

Communal

Talk to Your Neighbor About What You Learned Today

Speak with Others About Green Consumerism

Gift Experiences Rather Than Items/Stuff

TRANSFORMATIONal

Invest in Companies that Promote Reusability and Remanufacturing

Promote a Plastic Ban in Your Community